Latest FiTI TAKING STOCK transparency assessment provides unique insight into China’s fisheries

With the largest fishing fleet in the world – and as the biggest trader of seafood products – China is immensely important for global food & nutrition security and the sustainability of marine biodiversity. China also plays a critical role in the management of marine fisheries in many other countries, e.g. due to nation’s technical and financial support for fisheries development. In order to strengthen global understanding of how different countries approach transparency in marine fisheries management, the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI) evaluated the amount of fisheries information that national authorities in China make publicly available via government websites.

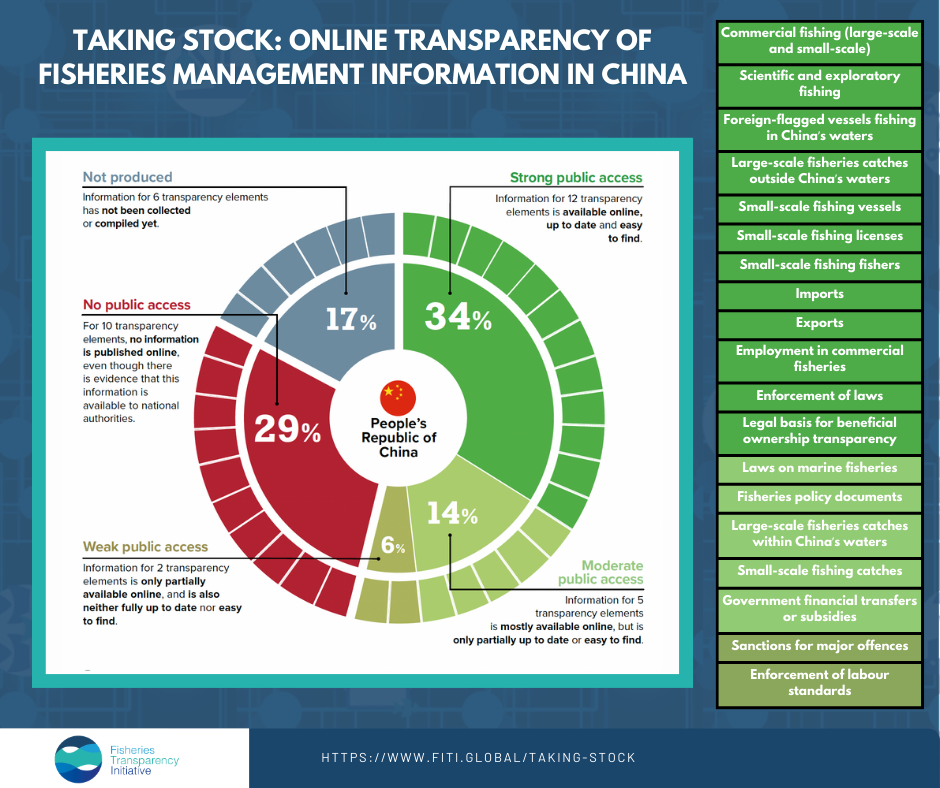

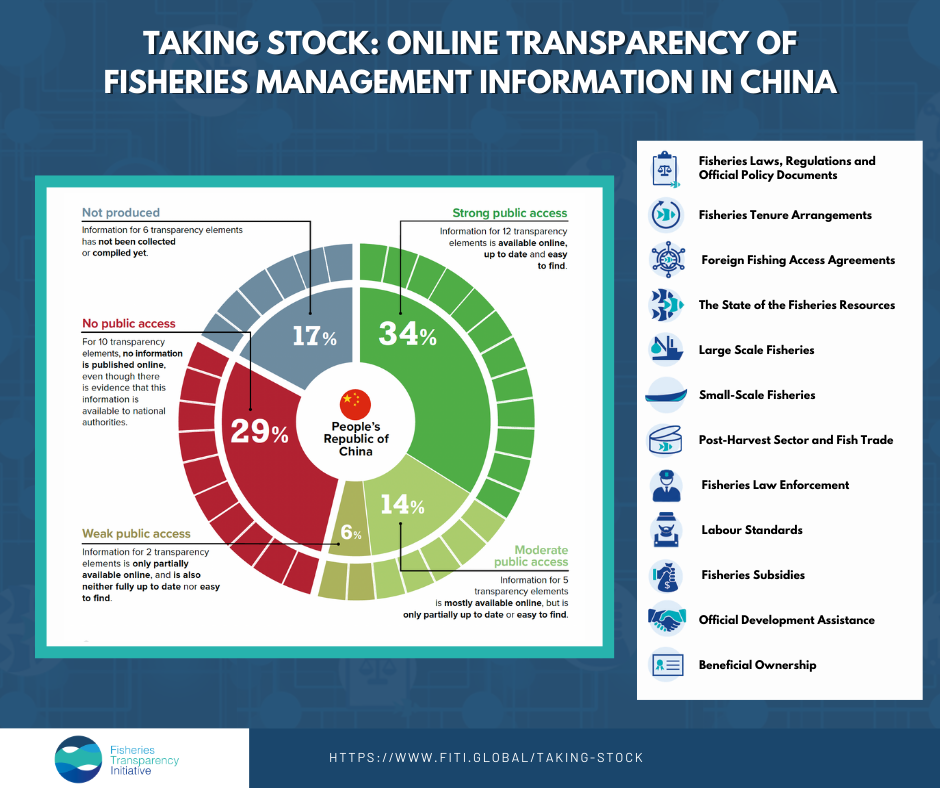

Overall, the results show that national authorities in China consider the collection and publication of online information on the fisheries sector to be an essential aspect of fisheries management. Notable examples include the publication of a detailed five-year plan for the fisheries sector with national objectives for fisheries development and measurable targets, and detailed annual statistical reports as well as a searchable public database with monthly reports on the imports and exports of seafood products.

At the same time, certain important information is not publicly accessible, such as the extent of overfishing in Chinese waters, the value and the recipients of government subsidies, or the nature of Chinese support to the development of fisheries in foreign countries. Furthermore, due to the complexity of China’s fisheries sector, locating this government information can be difficult.

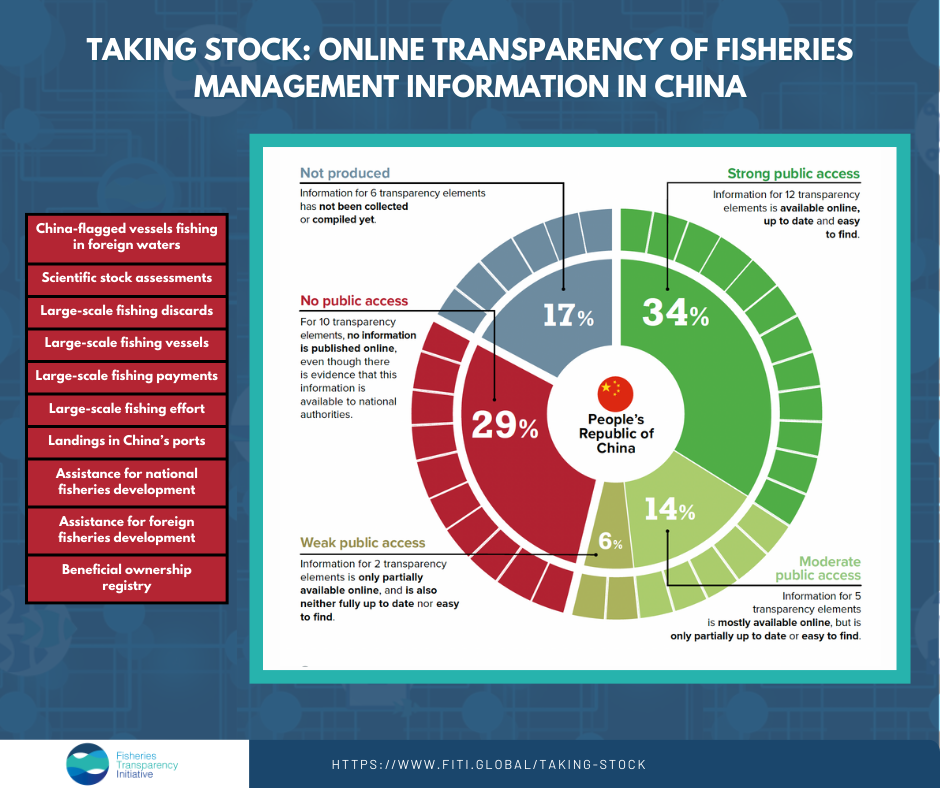

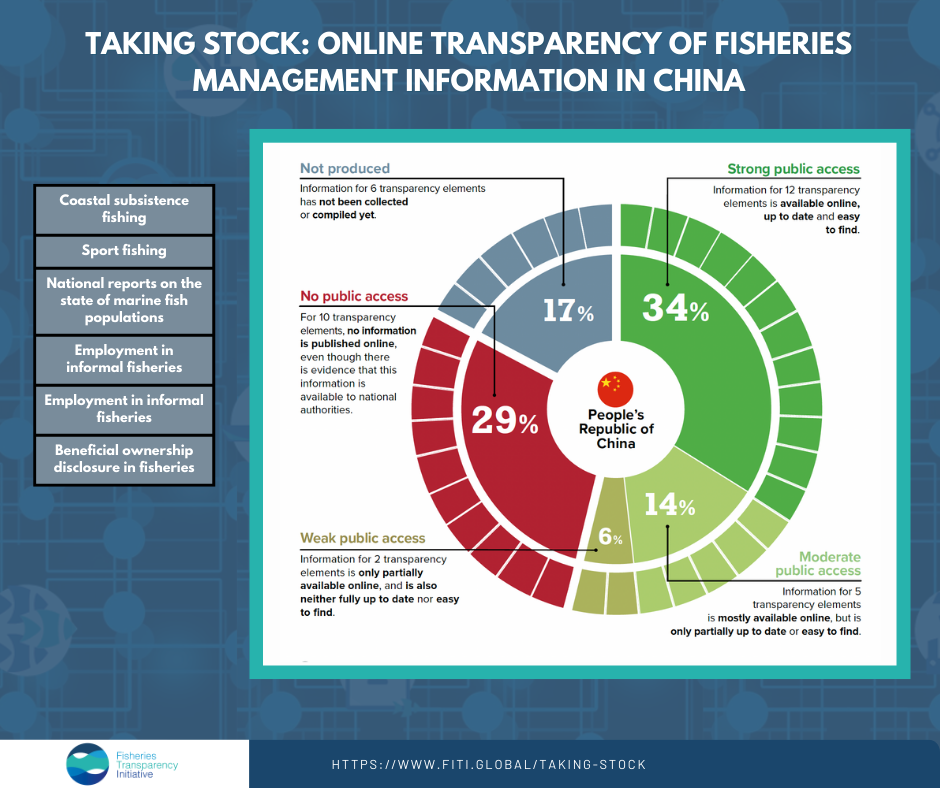

This latest TAKING STOCK transparency assessment provides a unique review of how China collates and organises information on its fisheries sector. Based on the 12 thematic areas of the FiTI Standard, this assessment reviewed 39 different transparency elements derived from the FiTI Standard, ranging from the publication of national laws, fisheries management plans, and vessel registries, to trade information, fisheries subsidies, and beneficial ownership. Furthermore, the assessment did not only evaluate whether information is publicly available and up to date but also the quality of this information in terms of its accessibility and reusability. Completing this assessment for China was particularly difficult given the size of its fisheries and the complexity of its fisheries management regime.

China’s national fishing authority, the Bureau of Fisheries, situated under the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA), publishes vast amounts of information online, including its flagship publication on fisheries, the China Fisheries Yearbook, which provides a detailed narrative of developments in fisheries management and extensive data on vessels and catches across coastal provinces. An annual Statistical Yearbook augments the Fisheries Yearbook, providing extensive communications on national fisheries policies and China’s long-term planning documents for fisheries development, including clear, measurable targets. China’s authorities publish information on the contracts of its reciprocal bi-lateral fisheries agreements with Japan, Russia, and Korea, as well as updates on the performance of these agreements, including the number of vessels operating and the volume of their catches. Additionally, China’s customs authority provides one of the most accessible and detailed databases on imports and exports of seafood products, with monthly reports on the imports and exports of seafood products, including information of the country of origin and destination. China’s data on trade also follows the Harmonised System established by the World Customs Authority.

However, the assessment found that some important information was also either hard to find or unavailable:

- Public information on the health of fish stocks in China is limited, despite evidence that authorities are undertaking regular scientific stock assessments.

- There is confusing and partial information on government subsidies. Improving transparency on this is crucial as China implements its ambitious Fishery Stewardship Subsidy.

- Although China provides extensive data on the catches of fishing vessels, the presentation of this data does not provide a clear picture of the catches made by small-scale fisheries compared to those of larger, industrialised vessels.

The assessment also recommends several improvements for increasing public access to information on China’s distant water fishing (DWF), including more granular data on catches. While over half a million fishing vessels are registered with Chinese national authorities, at least 2,500 Chinese-flagged vessels operating on the High Seas and in the waters of other countries. Given that the activities of China’s distant-water fishing fleet remain highly controversial and a source of criticism for the Chinese state, improving transparency of China’s DWF is not only a matter of national, but also of heightened international interest.

For example, in addition to reciprocal bi-lateral fisheries agreements between China and other countries (e.g. Japan), the vast amount of China’s fishing access agreements are usually private agreements between Chinese companies and foreign countries. These private agreements are currently not made public (unless published by the foreign country). China’s national authorities could insist that these contracts be made public, which would go some way towards addressing international criticisms over the Chinese DWF fleet’s lack of transparency. Additionally, Chinese authorities should provide comprehensive information on fisheries development projects funded through the Belt and Road initiative.

Finally, the TAKING STOCK assessment report lists considerable opportunities for Chinese authorities to address information gaps for Chinaʼs domestic fisheries, and advance transparency at the international level.

This assessment provides unique and valuable insights for fisheries policy debates in China and among international audiences. The results of the report will also contribute to FiTI’s efforts to enhance public understanding of how different governments approach transparency in marine fisheries management, with TAKING STOCK transparency assessments now undertaken in 11 countries (including in Peru, the United States), and more to come this year (e.g. Viet Nam and Indonesia).

The TAKING STOCK transparency assessment for China is available for download as a Summary Assessment Report as well as a complementary, in-depth Detailed Assessment Report here:

The TAKING STOCK assessment for China was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and carried out under the supervision and responsibility of the FiTI International Secretariat.